The assassination of the President J. F. Kennedy has been discussed and analysed for years and years, however, the deaths of other two writers has caught far fewer attention except for their specific researchers or devoted fans. This blog entry simply attempts to work out how each of them died individually and, hopefully, would like to align the deaths in chronological order.

As everybody knows, John F. Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas, Texas, on this day, while his ‘presidential motorcade was travelling through the main business area of the city’ (http://news.bbc.co.uk/onthisday/hi/dates/stories/november/22/newsid_2451000/2451143.stm). According to the article, the President was ‘hit in the head and throat when three shots were fired at his open-topped car’ (ibid) while the car was slowly passing through Dealey Plaza at about 13:25 local time. Soon after the shooting, ‘Mr Kennedy’s limousine was driven at speed to Parklands Hospital’ (ibid), and even ‘The president was alive when he was admitted’ (ibid), unfortunately, the article concludes that the President Kennedy ‘died at 1400 local time (1900 GMT)’ (ibid).

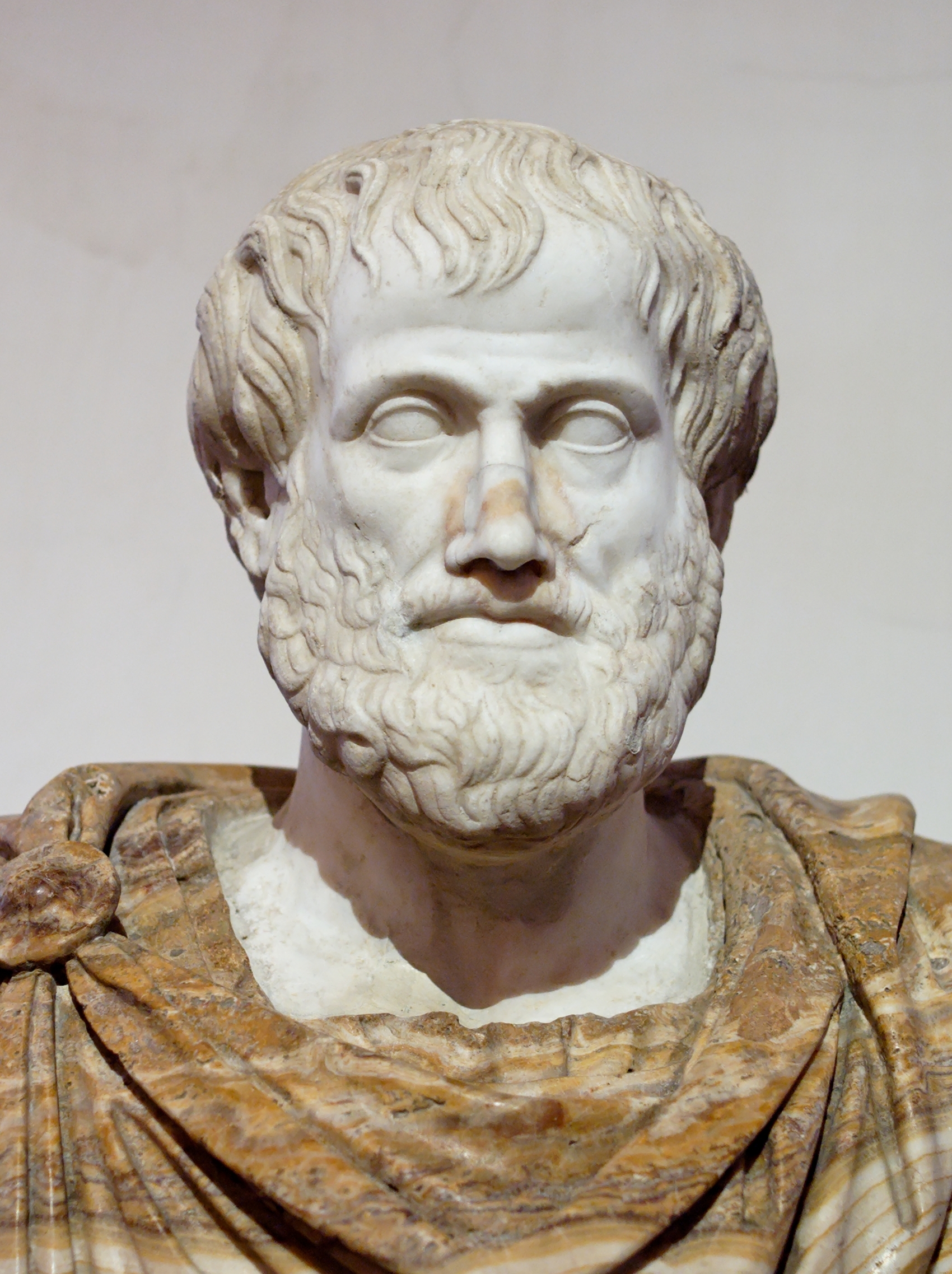

|

| John F. Kennedy |

Approximately an hour before J. F. K was hit, at about 18:25 in Greenwich Mean Time, C. S. Lewis died at his home called The Kiln, where he had been living since 1929, in Oxford, England. It is said that ‘He had resigned his position at ( the Chair of Medieval and Renaissance Literature at) Cambridge (that he had accepted in 1954) during the summer’ due to his health issues and he ‘died at 5:30 p.m… on Friday, November 22, after a variety of illnesses, including a heart attack and kidney problems’ (http://cslewis.drzeus.net/bio/).

Finally, as for the time and circumstance of Aldous Huxley’s death, it can be confirmed that he ‘died of cancer at home in Hollywood on 22 November 1963, unaware that President J. F. Kennedy had been assassinated earlier that afternoon in Dallas’ (Bradshaw, 2005, p xiv)*. Although sources like Wikipedia give the concrete time of his death; at 5:20 pm in local time, since sources like this are usually regarded as untrustworthy in academic fields, this blog decides to satisfy with providing the chronological order of the deaths as; (1) C. S. Lewis at 17:30 GMT, (2) John F. Kennedy at 19:00 GMT and (3) Aldous Huxley at later than both of them.

*Bradshaw, David (2005), Biographical Introduction for The Devils of Loudun by Aldous Huxley